Green Tea Brewing Temperature Guide

Have you ever noticed how the same green tea can taste fresh and sweet one day, then dull or bitter the next? The difference often comes down to one simple factor — temperature. Even a small change in water heat can dramatically alter the flavor, aroma, and nutrient profile of your tea.

Most people focus on the brand or type of green tea they buy, but the real secret to a perfect cup lies in how you brew it. Each variety — from delicate Gyokuro to bold Hojicha — has its own ideal temperature range that brings out its best qualities. Too hot, and you scorch the leaves. Too cool, and the flavor falls flat.

This guide breaks down the science behind brewing temperatures and gives you precise recommendations for every major type of green tea. You’ll learn how heat affects taste and health benefits, and how to control temperature even without a thermometer — ensuring every cup is balanced, smooth, and vibrant (1).

Why Temperature Matters in Brewing Green Tea

Brewing tea is a form of gentle chemistry. When hot water meets tea leaves, it extracts natural compounds — catechins, amino acids (like L-theanine), and caffeine — each responsible for specific flavors and effects. Temperature determines which compounds dominate in your cup.

At higher temperatures, more catechins and tannins dissolve quickly, creating a bitter, astringent taste. Lower temperatures favor L-theanine, the amino acid that gives tea its mellow sweetness and calming effect. The balance between the two defines your tea’s character.

Research shows that brewing green tea at lower temperatures (around 70–80°C or 158–176°F) maximizes L-theanine extraction while minimizing bitterness from catechins (2). Conversely, hotter water boosts antioxidant yield but can compromise smoothness. Finding your ideal temperature is therefore a matter of taste — and purpose.

Factors That Affect Ideal Brewing Temperature

There’s no universal “perfect temperature” for all green teas. Several factors influence how much heat each variety can handle without becoming bitter or flat. Understanding these variables helps you fine-tune your brewing method and bring out each tea’s unique character.

1. Type of Tea (Shade-Grown vs. Sun-Grown)

Green teas grown in the shade, such as Gyokuro and Matcha, contain higher levels of L-theanine and chlorophyll, which contribute to their smooth, umami-rich taste. These delicate compounds degrade easily under high heat. That’s why shaded teas require cooler water — usually between 55–70°C (131–158°F) — to preserve their natural sweetness.

By contrast, sun-grown teas like Sencha and Bancha develop more catechins from sunlight exposure. These can withstand higher temperatures, around 75–85°C (167–185°F), without turning harsh (3).

2. Leaf Size and Shape

Whole, rolled, or flat leaves release flavor more slowly than crushed or powdered ones. Teas like Dragon Well (Longjing) or Sencha are best brewed with moderately hot water, while finely ground teas such as Matcha require lower heat to prevent clumping and bitterness.

Smaller or broken leaves have a larger surface area, so they extract faster. When using these, slightly lower your water temperature or reduce steeping time to maintain smoothness.

3. Water Quality and Mineral Content

The quality of water is as important as its temperature. Hard water — rich in minerals like calcium and magnesium — can dull flavor and emphasize bitterness. Soft or filtered water allows more delicate aromas to emerge and supports even extraction of antioxidants and amino acids.

Tea experts often recommend using fresh, filtered water that’s just boiled and then cooled to the desired temperature. This ensures oxygen is preserved, which helps enhance the tea’s fragrance and texture.

4. Brewing Method and Equipment

Different methods distribute heat differently. A Kyusu teapot (Japanese clay pot) retains warmth efficiently and suits lower temperatures, while thin glass teapots cool faster and are better for precise, lighter brews.

Electric kettles with temperature control offer accuracy, but you can also estimate by timing: boiling water generally cools to 80°C (176°F) after sitting uncovered for about 2–3 minutes. Traditional Japanese brewing often uses a “cooling pour” method — transferring water between cups to lower heat naturally and gently.

5. Steeping Time and Leaf Quantity

The longer the leaves remain in contact with hot water, the more compounds are extracted. If you’re unsure of the right temperature, you can compensate slightly with time: cooler water and longer steeping produce milder, rounder flavors. Too much leaf or heat, however, can quickly lead to bitterness.

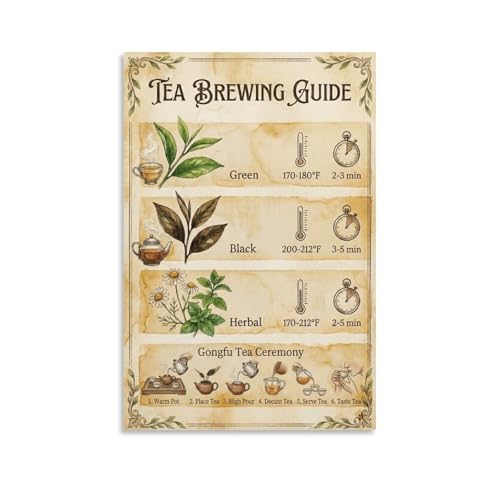

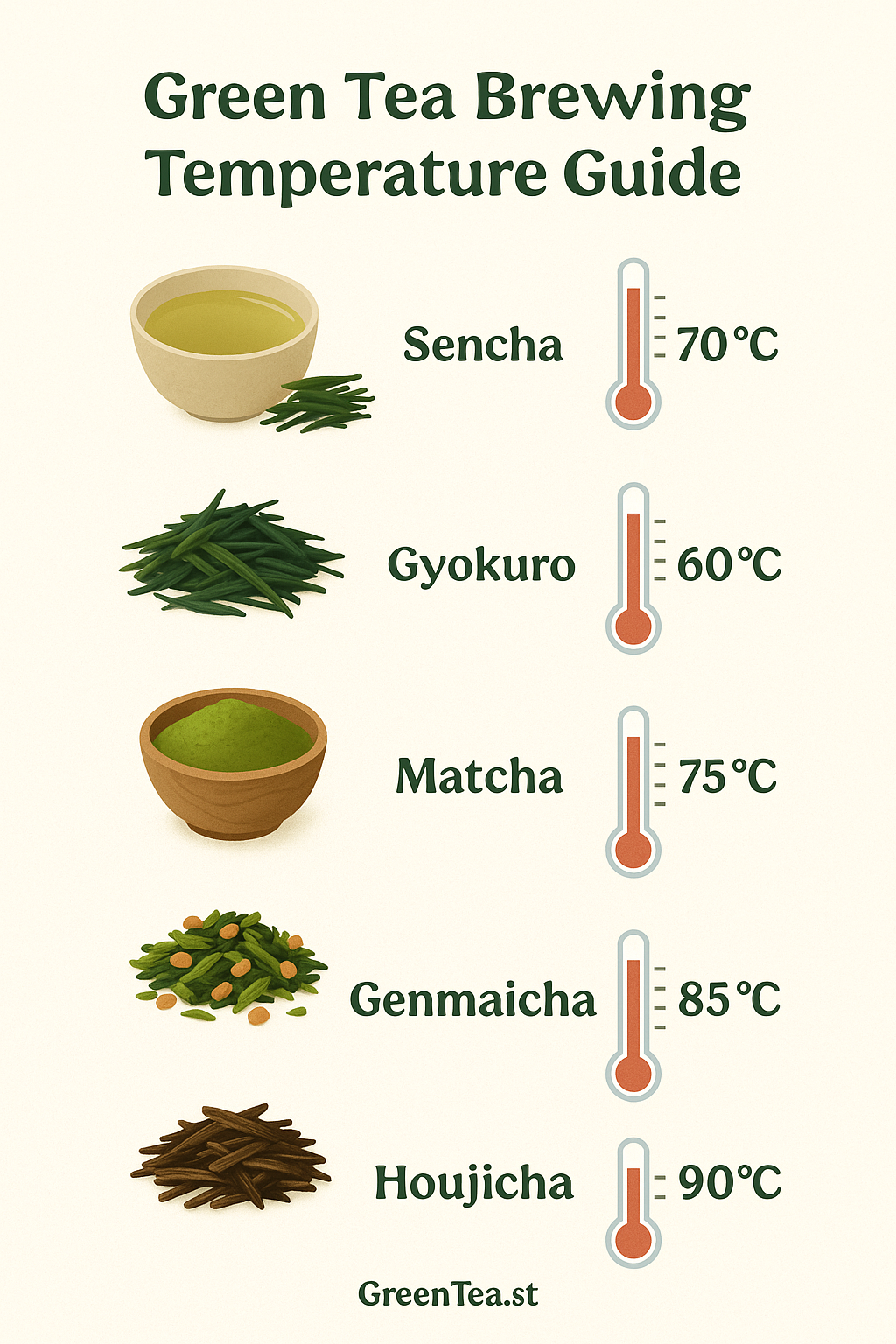

Recommended Brewing Temperatures by Tea Type

Every variety of green tea has its own flavor balance and sensitivity to heat. Brewing at the right temperature ensures you extract the perfect mix of sweetness, umami, and aroma without tipping into bitterness. Below are the recommended temperature ranges and explanations for six of the most common green teas.

1. Sencha (Classic Japanese Green Tea)

Ideal Temperature: 75–80°C (167–176°F)

Sencha is Japan’s most popular green tea, loved for its grassy, slightly sweet taste. At this moderate temperature, the balance between catechins and L-theanine remains stable, creating a crisp yet smooth flavor.

Brewing Sencha too hot (above 85°C) draws out excessive catechins, leading to astringency. Conversely, water that’s too cool can leave it tasting flat. Proper heat brings out the tea’s signature bright aroma and clean finish (4).

2. Gyokuro (Shade-Grown Premium Tea)

Ideal Temperature: 55–60°C (131–140°F)

Gyokuro is among the most delicate and prized Japanese teas, grown under shade for several weeks before harvest. This process increases chlorophyll and L-theanine, producing an intensely sweet, savory flavor known as umami.

Low brewing temperatures are crucial — anything hotter than 65°C destroys the amino acids that give Gyokuro its buttery texture. Brewing slowly with cooler water yields a thick, smooth liquor with a long-lasting sweetness (5).

3. Matcha (Powdered Green Tea)

Ideal Temperature: 70–80°C (158–176°F)

Matcha is unique because you drink the entire powdered leaf rather than steeping and discarding it. Too-hot water makes it clump, creating a sharp, bitter taste. Use slightly cooled water and whisk briskly in a zigzag motion to produce a creamy, frothy surface.

When brewed within this range, Matcha maintains its signature smoothness and delivers high antioxidant and L-theanine content without harshness (6).

4. Hojicha (Roasted Green Tea)

Ideal Temperature: 90°C (194°F)

Unlike most green teas, Hojicha is roasted over charcoal, giving it a deep, nutty aroma and reddish-brown color. Its low catechin content makes it less sensitive to heat, so hotter water enhances its toasty sweetness and mild caramel undertones.

Brewing Hojicha below 85°C often results in a weak flavor, while boiling water intensifies its comforting roasted notes without bitterness (7).

5. Genmaicha (Green Tea with Roasted Brown Rice)

Ideal Temperature: 80°C (176°F)

Genmaicha combines green tea leaves with roasted brown rice, creating a nutty, balanced cup with low caffeine and gentle sweetness. Brewing around 80°C allows both the tea and rice to release their flavors evenly.

Water that’s too hot can overpower the rice’s toasty aroma, while cooler water may leave the infusion bland. At this temperature, the blend remains soft and aromatic (8).

6. Bancha (Everyday Japanese Green Tea)

Ideal Temperature: 85°C (185°F)

Bancha is harvested later in the season, producing coarser leaves with lower caffeine but higher tannin content. It’s well-suited for a slightly hotter brew, which draws out its warm, earthy notes and mild sweetness.

Brewing below 80°C can mute its flavor, while boiling water may create bitterness. A steady 85°C maintains its balance and brings out its comforting aroma (9).

How to Control Temperature Without a Thermometer

You don’t need a digital kettle or a barista’s toolkit to brew green tea at the right temperature. With a bit of observation and timing, you can easily control heat levels using simple cues. The goal is precision through awareness — not equipment.

1. Let the Water Cool Naturally

Once water reaches a full boil, take it off the heat and let it sit uncovered.

- 1 minute of cooling = ~90°C (194°F)

- 2–3 minutes = ~80°C (176°F)

- 5 minutes = ~70°C (158°F)

This method works for most teas. For example, you can brew Sencha after two minutes of cooling or Gyokuro after five. The key is patience — even a short rest can make the difference between bitter and beautifully balanced tea.

2. Use the “Pouring Method”

A traditional Japanese technique called yuzamashi cools water gently without measuring. Pour the freshly boiled water from the kettle into an empty teacup, then into the teapot holding the leaves. Each transfer lowers the temperature by about 5–10°C (9–18°F).

This method is especially effective for delicate teas like Gyokuro or Matcha, where precision matters but thermometers aren’t practical. It also helps oxygenate the water, enhancing aroma and texture.

3. Watch the Steam

Visual cues can tell you a lot.

- Large bubbles and strong steam: ~95°C (203°F)

- Gentle rising steam: ~85°C (185°F)

- Barely visible steam: ~75°C (167°F)

This old-fashioned approach, used in traditional tea houses, trains you to connect visually with your brewing process rather than rely on gadgets. Over time, you’ll recognize the sweet spot by sight alone.

4. Use Cold Water to Adjust

If the water still feels too hot, add a tablespoon or two of cold, filtered water to the pot before pouring it over the leaves. This small adjustment can drop the temperature by 5–7°C, softening the brew instantly.

5. Invest in a Temperature-Control Kettle (Optional)

For those who brew multiple teas or want consistent results, an electric kettle with temperature presets is a worthwhile investment. Models with 50°C–100°C range options make it easy to switch between teas like Gyokuro and Hojicha with one button.

But even without it, traditional cooling and timing techniques remain just as effective and sustainable (10).

Brewing Tips for a Balanced Cup

Perfecting green tea is about consistency and mindfulness. Once you’ve mastered temperature control, small adjustments in teaware, timing, and water quality can take your brew from good to exceptional. These steps fine-tune flavor, texture, and aroma — without complicating the process.

1. Pre-Warm Your Teapot and Cups

Before brewing, rinse your teapot and cups with a bit of hot water. This stabilizes the brewing temperature so the tea doesn’t cool too quickly when poured. Pre-warming is especially useful for delicate teas like Gyokuro and Sencha, which can lose flavor intensity if the temperature drops too soon.

This step also enhances aroma — a warm cup releases more fragrance when the tea is poured.

2. Avoid Metal Teapots for Green Tea

While metal kettles are fine for boiling water, avoid brewing directly in metal containers. Metal can subtly alter taste, especially with softer, more fragrant teas.

Use ceramic, glass, or porcelain teapots, which distribute heat evenly and maintain flavor purity. Clay teapots, such as Japanese Kyusu, are excellent for holding lower brewing temperatures and enhancing the tea’s smoothness.

3. Use Filtered Water Whenever Possible

Because tea is nearly 98% water, quality matters enormously. Hard water with high mineral content often flattens flavor and exaggerates bitterness. Filtered or soft water allows amino acids like L-theanine to shine, resulting in a sweeter and cleaner cup.

If your tap water has a strong chlorine or metallic taste, switch to filtered or spring water. Research shows that lower-mineral water improves antioxidant stability and aroma release in brewed green tea (11).

4. Stick to 2–3 Minutes for Steeping

Even at the right temperature, steeping time determines flavor depth.

- Green teas: 2–3 minutes

- Oolong: 4–5 minutes

- Black teas: 4–6 minutes

Leaving the leaves too long, even in cooler water, can release extra tannins. Use a timer if needed — consistency builds muscle memory, and your palate will reward you.

5. Reuse Leaves Mindfully

High-quality loose-leaf green teas, such as Sencha and Dragon Well, can be re-steeped once or twice. For the second brew, slightly increase the temperature (by 5°C) but reduce the steeping time by half. This brings out new layers of sweetness without bitterness.

Avoid reusing old leaves after more than a few hours; oxidized leaves lose flavor and freshness quickly.

FAQs

Using boiling water over-extracts tannins and catechins, making your tea taste bitter and dry. It can also destroy delicate amino acids that give green tea its sweetness and aroma.

It’s best not to. Matcha should be whisked with water between 70–80°C (158–176°F). Hotter water causes clumping and burns the powder, producing a harsh taste instead of smooth creaminess.

Each tea’s leaf structure and processing method affect how it reacts to heat. Shade-grown teas like Gyokuro are rich in L-theanine, which is heat-sensitive, while roasted teas like Hojicha tolerate higher temperatures due to lower catechin content.

Yes. Lower temperatures extract less caffeine, which makes cold brews or cool infusions ideal for those sensitive to stimulants. The result is smoother, slightly sweeter tea with less bitterness.

Reheating breaks down antioxidants and dulls flavor. If your tea cools, drink it at room temperature or make a fresh cup instead. For longer sessions, use a small thermos to keep tea warm without reboiling.

Conclusion

Temperature is the heartbeat of tea brewing. It determines not only how your cup tastes but how it feels — bright or bitter, smooth or sharp, soothing or stimulating. Mastering heat gives you complete control over your tea’s character.

Lower temperatures bring out sweetness and umami; higher ones enhance aroma and strength. The key is to match the temperature to the tea’s personality. Once you learn that balance, every brew becomes more intentional and rewarding.

Brewing tea with care is more than a habit, it’s a ritual of patience and precision. Whether you’re whisking Matcha, steeping Sencha, or roasting Hojicha, the right temperature turns a simple cup into an act of mindfulness and nourishment.